The Zebra Murders: Civil Rights, Racial Revolution, and San Francisco's Season of Horror - Part 3

In 1973, a black nationalist cult in San Francisco sought to eliminate the white race. Their reign of terror made them the most prolific murderers of the counterculture. What were the Zebra murders?

You should read Part 1 and Part 2 first.

As the police canvassed another neighborhood, combing through alleys, taking witness statements, looking for bullet casings, Mayor Joseph Alioto contemplated the dour evening that laid ahead of him. After almost three months of silence, there were five murder attempts in the last two weeks, each with the same profile, the same eyewitness descriptions, and the same gun. Scores of new police officers had been hired and put on patrols, and yet the key suspects escaped again—likely on foot. With a sigh, Alioto stepped into the car that pulled up outside his home, and started mentally rehearsing his monologue for the upcoming press conference.

Alioto was a born-and-bred San Franciscan, old school to his core. He was born in 1916, a second generation immigrant coming from Sicilian stock that went west after Ellis Island. Alioto’s parents were quite wealthy, and his early life followed the standard arc of the Catholic upper-class of prewar San Francisco. He went to school at Sacred Heart, followed by college at St. Mary’s, before cutting his teeth as a lawyer in the Justice Department. In 1967, after the all-but-anointed mayoral nominee died unexpectedly, Alioto edged out a victory in a race with 18 candidates. He campaigned as a “return to normalcy candidate,” capitalizing on the collective disgust aroused by that year’s “Summer of Love” (and the winter of discontent that followed). In 1971, Alioto won reelection (over future Senator Dianne Feinstein) in another campaign dominated by traditionalist candidates.

Alioto wasn’t a machine politician, but he deeply resembled one. He drew his base largely from trade unions, whom he rewarded with political appointments and favors, like blocking non-labor building projects or hampering efforts to automate the port. He also had support from the teachers and civil service unions, which he affirmed every year by fighting the state’s mandate for mandatory busing. The final buttress in this tripod was nepotism, which he engaged in so unabashedly that it drove even his political opponents to question their convictions. In 1974, Alioto was working on courting the police union, SF’s other major power broker, whose support was essential to maintaining his image as a law-and-order reformer.

This was especially important because, in 1974, San Francisco was not a city of law-and-order. The streets were not safe, neither in daylight nor after dusk. The sidewalks were filthy. Homelessness was rife. In February, Patty Hearst, the granddaughter of William Randolph Hearst, had been kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army. And in the last three weeks, psychotic black cultists had attempted to murder five people, succeeding in killing two. Alioto’s position was thus politically fraught. He was a conservative, pro-police mayor presiding over the largest crime wave in the city’s history. His police force, whom he had just made the highest paid in the country, had no suspects and few prospects for surfacing any.

On April 17th, the day after Nelson Shields was murdered, Alioto and Donald Scott, SF’s police chief, announced Operation Zebra. From the next day onwards, the police would implement a massive stop-and-frisk policy in San Francisco. Any black man with any resemblance to two composite sketches, assembled from the various eyewitness descriptions, was liable to be stopped and searched. Police patrols would be once again be expanded, both in number and in the area they covered. Alioto had decided, in utter desperation, that this drastic, likely illegal program was his only option to catch the murderers—and save his political career.

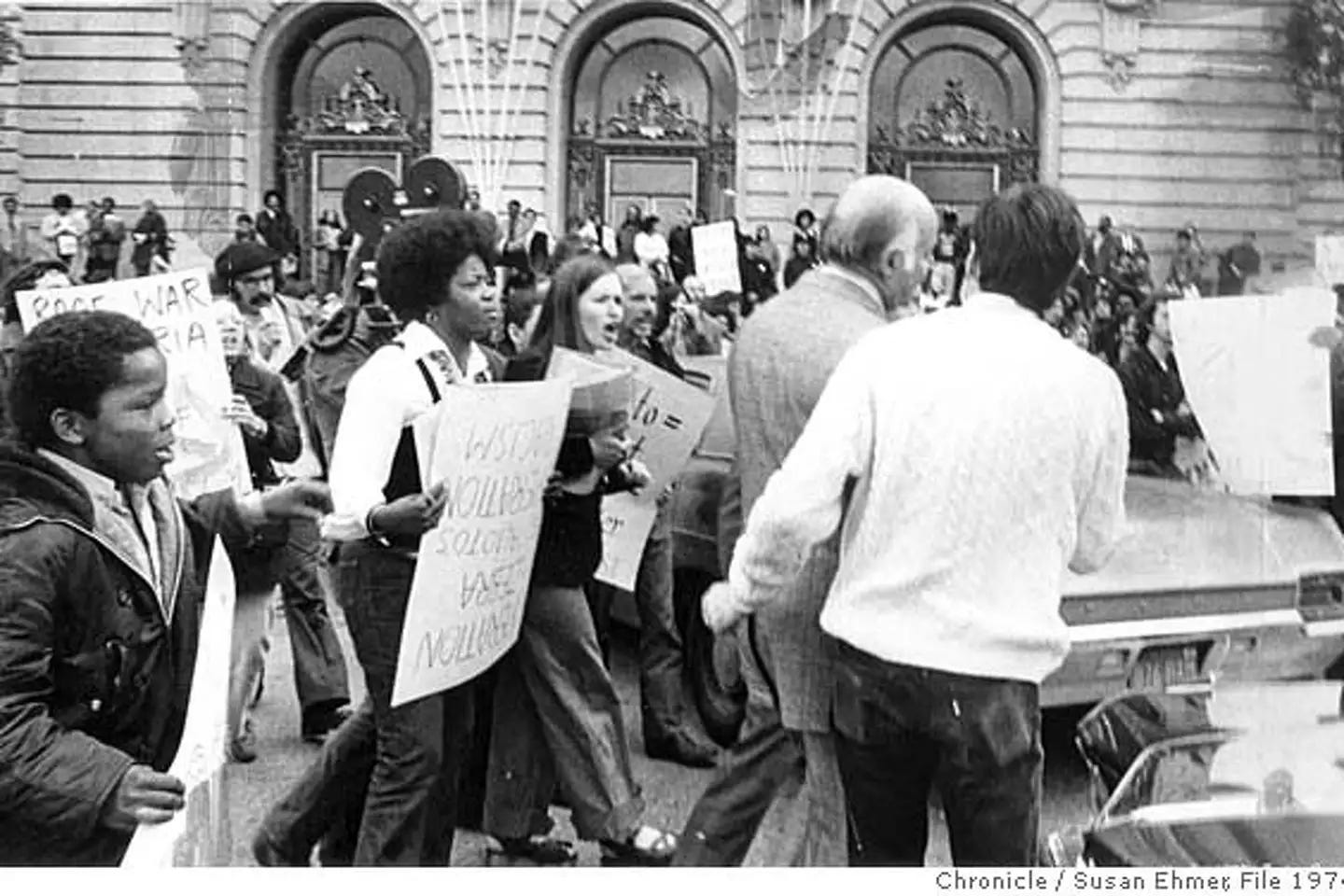

Immediately, there was chaos. The two black detectives in homicide department walked out in fury. The ACLU and the NAACP both launched lawsuits, seeking an injunction. There were protests outside city hall, where activists attacked Alioto with picket signs before he could escape into a waiting car. The next day, neo-Nazis, accompanied by other white supremacist groups, staged a counterprotest, offering to escort the police officers making searches. Bobby Seale, the Black Panther leader, himself a black separatist intent on inciting racial violence, commented that police, who were also searching for Patty Hearst, would never arbitrarily stop white women on the street.

Over the first two days, police searched almost 200 black men. After multiple duplicate stops, they began issuing “Zebra cards:” documents with an individual’s name, address, and driver’s license number that indicated they had already been cleared. A black nurse, Monique Von Clutz, made a public speech that compared these to the black identification cards used in what she called "the racist Union of South Africa."

The white public was overwhelmingly in support of the stops. Their opinions were reflected in the Chronicle, which wrote that the action was a last resort, and that “the police deserve every citizen's cooperation,” for finding the killers is a benefit to everyone. In strict terms, that was correct. And yet, as each day passed, the search grew coarser, the stops became increasingly arbitrary, and frustration built. Police stopped doctors and lawyers, men obviously too old to be a suspect, or young children who were never under suspicion. Kemp Dawson, a fifty-nine year old, fair skinned, 5’9, 255-pound man, was walking near Booker T. Westbrook, a seventeen-year-old, six feet tall, 155-pound, black high school student. Both were stopped, and afterwards, each wondered how they could both fit the same set of eyewitness accounts. And even worse, police often used the stops as a chance to search for outstanding warrants. Many black men, innocent of murder, were hustled to jail after they were booked for overdue traffic tickets.

The latent racial divisions in San Francisco, exposed by the murders, now threatened to widen into fissures. On the fourth night, an elderly black man walking in the Fillmore was stopped by a plainclothes cop. In a panic, thinking he was being attacked, the man pulled out a pistol and started firing. Several other cops in the vicinity all began firing at the man, who collapsed. He later died. That same evening, just south of Market, a brawl broke out between a group of black men and a mixed group of police officers accosting them. Two black patrolmen were able to separate the groups, until a different set of white cops started attacking them with truncheons. The black patrolmen joined the stopped men to resist their colleagues, leading to police officers fighting each other on the streets.

Finally, on April 25th, a federal judge enforced an injunction against the operation, calling it “unlawful search and seizure,” which violated the fourth amendment. Barely a week after it began, Operation Zebra was terminated. It didn’t generate any new suspects, didn’t create any new leads, and didn’t surface any new evidence. Mayor Alioto’s gambit was a complete failure.

The day before Operation Zebra was announced, Gus Coreris, one of the two detectives leading the Zebra investigation, was at a loss. He’d talked to each of the survivors of the most recent attacks, and not a single one could offer a useful description of their assailant. 5’10. Black. Perhaps 25-30? Not sure about hairstyle. Brown eyes - maybe? As Coreris scrawled the disembodied snippets down, his face fell. Those characteristics matched almost half of the young black men in San Francisco.

But as he contemplated further, Coreris realized something else. At this point, he had taken so many witness statements, adjusted so many composite sketches, that he had developed his own images of the three killers in the black Cadillac. The driver, large, lumbering, imposing. The passenger, lanky, tall, forceful. And the man in the backseat, who was only witnessed at one scene, and was the only one who had ever struggled with his victim.

With no other leads, Coreris went to Hobart Nelson, SFPD’s sketch artist, and described his recollections with as much detail as he felt comfortable with. That composite sketch made its way to Donald Scott, who authorized it for use in the Operation Zebra sweeps, and then to the Bay Area presses, which plastered it on every front page. One of those newspapers circulated in Oakland, and one of the April 17th editions found its way to the dining table of Anthony Harris. When Harris looked at it, he felt his stomach drop in horror.

The image on the front page was him. The eyes, the bushy hair, the long nose—it was unmistakably him. Harris shuddered. He looked out his window and felt eyes crawling over him, then retreated in a gasp. They had him. The police knew what he looked like. He couldn’t go to the NOI, he couldn’t escape from Oakland, and now, he couldn’t even go outside. Harris buried his face into his pillow, shaking with fear, and agonized about what to do next.

Only one real option surfaced in his mind, but he rejected it. For now.

On April 24th, the day after Operation Zebra was officially ended, Gus Coreris and his partner, Jon Fotinos, glumly sat in the corner of Homicide, chain-smoking cigarettes and fruitlessly combing over old leads. Coreris and Fotinos had been working the case since the murder of Saleem Erakat and the first indication that the killings, seemingly random, may be part of some overarching pattern. Both were hardened detectives with over a decade of service at every level of policing, but now, after almost six months of hysteria, political pressure, sixteen hour days, an excess of caffeine and alcohol, and almost nothing to show for it, they were becoming despondent. So, when the phone rang on Fotinos’ desk, its shrill urgency piercing their midafternoon lethargy, neither man moved.

Instead, Jeff Brosch, a junior detective recruited onto the case, walked over from the next room and picked it up. The gruff voice on the other side said he had information relating to the case, and he wanted someone to meet him in Oakland. All of the detectives looked at each other in exasperation. The only constant of the Zebra case so far was the glut of tips. Tips arrived with such frequency that during the murderers’ hiatus, the four man investigation team was turned into a peripatetic court akin to that of monarchs of old, who traversed their realms, retinue in tow, to hear complaints and dispense justice. In this case, however, the monarchs only heard either obvious deceptions, the ramblings of the deluded, or transparent racism, and could offer their subjects little but their shared frustration. The two older detectives, expecting more of the same, were unwilling to rise from their languor, and tasked Brosch with crossing the bridge to take a statement.

Anthony Harris hung up the payphone and stood in the booth awhile, retracing with his eyes the number he’d typed on the keypad. Idly, he wondered if he’d just signed his own death warrant. A second later, he dismissed the thought—on his current path, his death was assured. His conversation with Larry Green a few days before made that clear. Green told him, in no uncertain terms, that the brothers weren’t searching for him yet, but they would. And when they found him, he ought to have a good explanation for his absence. Harris shook his head in dismay. Green was a friend—an old one, before the Nation of Islam and the Death Angels. If Green was threatening him, then there was no safe place left. Talking to the police was his only remaining alternative.

Jeff Brosch stepped out of his cruiser in a parking lot in west Oakland, close to the bridge. To his right, shipping containers, stacked ten-high, stretched almost to the horizon. Callused, rough men, hardened by years of labor, operated cranes that dangled the containers in the air before lowering them onto the dock. This must be a daily ritual, Brosch thought. He considered its religious regularity, the precision of its timing. The ships would always dock. The containers would always arrive, one after another, stacked ten-high, stretching to the horizon. How easy it would be for a man to be crushed beneath one, Brosch thought. How easily life could be extinguished. Brosch wondered how many died on those docks each year. He wondered how much each investigation went into their deaths, and whether every longshoreman was interrogated when it happened. Suddenly, out of the corner of his eye, Brosch saw a black man walk towards him. He realized that the lot, deserted, obscured by trees, was an ideal ambush spot. His own flesh-and-bone fragility flashed before his eyes.

But Anthony Harris came alone and unarmed. He told Brosch he had information about the Zebra murders. Brosch, skeptical, asked what he had. “It was the Death Angels. They think all the whites are blue-eyed devils and they kill them. Men, women, children, everyone.” The mention of children piqued Brosch’s interest. “What children do you mean?” he asked. “The three kids they tried to grab the night they hacked the woman.”

Brosch froze. He knew exactly what Harris was referring to. Two hours before the Hagues were attacked, three eleven year olds had reported that two black men had grabbed them and attempted to drag them to a van. The children had managed to distract their assailants, giving them a second to run away. None of them could give a good description of the two black men, but they remembered the van: a Dodge, dark colored, with a logo emblazoned on the side. After the Hagues were attacked, the similarities in the suspects, the van, and the timing, made connecting the two crimes obvious. But, because the abduction was a failure and the victims were minors, the incident was never mentioned in the press. Brosch was almost certain there wasn’t a single article mentioning the abduction. He looked at Harris now with newfound confidence. This man knew something.

Brosch drove back to San Francisco with Harris, where he was placed in an interrogation room with Coreris and Fotinos. Harris was reticent at first, but as the two seasoned detectives pushed, he started speaking, gaining momentum as he went on. Harris started with the kids, the Hagues, the train tracks, how Quita Hague had been raped. He spoke on Saleem Erakat, whom he called a Mexican. Then the attacks on Paul Dancik and Marietta Giralamo and Illario Bertucci and the rest. The package he dumped in the ocean. The night of four murders. Over time, he started giving names too. J. C. X Simon was the leader of their group, personally responsible for organizing the stings. Manuel Moore, the moveable dope with a murderous edge. Jesse Lee Cooks, already imprisoned. And Larry Craig Green, Harris’ old friend, who had threatened his life just last week. Harris also named four other men—Thomas Manney, Dwight Stalling, Edgar Burton, and Clarence Jamerson—who worked at the Black Self-Help Moving Company. Thomas Manney allegedly owned the black Cadillac present at so many of the murder scenes.

The investigators did realize, however, that Harris’ story had a number of gaps. Despite providing eight names, Harris could only place Simon, Green, Cooks, and Moore at a crime scene. And, they noticed, Harris never mentioned his own role in any of the killings. Every statement was phrased with a “they” or a “them,” even as the descriptions he gave required a first-person view. Harris did, however, give a number of important details. He mentioned a .32 automatic that Simon owned. He described several instances of finding unexplained bloodstains in the moving van. He described the Death Angels’ meetings, in the loft or the Mosque. By the end, the Zebra team was convinced that Harris was a legitimate informant, and despite his stated desire to claim the thirty-thousand dollar reward, his confession seemed authentic.

Harris wanted personal immunity and feared for his wife and child. Both detectives immediately offered protection for his family, but immunity was contingent on his testimony in court. Perhaps three months ago they would have bargained further, pushing for a plea deal instead of outright immunity, but right now, with the entire city of the verge of fratricidal conflict, they only cared about ending the killings.

Harris, his wife Deborah, and his new child, were lodged in the Holiday Inn next to the Hall of Justice. The interrogations continued in the hotel room the next morning. As Harris spoke more, the overall narrative of the murders began to take shape. And as it did, Harris’ refusal to place himself at any crime scene became increasingly absurd. Coreris and Fotinos realized that his insistence would collapse under cross-examination, and began to officially organize immunity for Harris. Perhaps when he was assured of exoneration, he would share his own culpability.

Meanwhile, at the front desk, a well-dressed black man was talking to the desk clerk. “Do you have Anthony Harris registered?” he asked. They did. The man asked to speak to Harris, and was put through. “Can I come up?” he asked. “No,” Harris replied. “Why don’t you come down then?” Harris hung up, knots of fear pulsing through him. He immediately told Coreris, and both looked at Deborah. That morning, Deborah was feeling nervous, and insisted on speaking to her friend, Sister Sarah, the wife of a high-ranking NOI minister. Harris looked at her. “Did you mention where we were staying?”

“I might have.”

Coreris, Fotinos, and Harris looked at each other. All of them knew what the unknown man had come here to do. The two detectives left the room and took the elevator to the lobby, where Coreris saw the black stranger idling near the front desk. Coreris walked up to him and asked, “what are you doing?” “Waiting for some friends,” came the response. Coreris paused, and glanced at the glass hotel doors. Just then, a black Cadillac pulled up and five men stepped out. The two detectives looked at each other. “Get to parking,” Fotinos whispered, and then the two split up. Fotinos ran to the elevators and went up. Coreris sprinted out the front door just as the group of Muslims walked in and moved towards the stairs.

Coreris ran to his car, parked just behind the building, and sped towards the spiral parking structure next to the hotel. He accelerated up the structure, flashing past pillars and careening around tight corners. The Muslims ran to Harris room, only to find it unlocked and empty. They scanned the floor, then moved up to the next. Coreris kept charging up the ramp. The Muslims took the stairs to the next floor, and then the next. Each floor was silent, empty, quiet. Finally, they reached the roof and vaulted through a side door, only to hear tires screech and see a car disappear into the descending coils.

Harris and Deborah were moved to the Stewart hotel near Union Square. The Muslims, so close from their prize, started canvassing every hotel near downtown San Francisco. This time, the front door clerk was given strict instructions to deny the existence of any guest named Anthony Harris to anyone that asked.

Later that day, when Coreris returned to his desk, he listened a voicemail from a patrol officer asking to meet with him. Coreris called him back, and the officer arrived shortly after. The officer asked him if he was holding someone named Anthony Harris.

“Why?” Coreris replied.

“Where is he being held?” said the officer.

“Who is asking?” Coreris deflected.

“Some friends of mine.”

“Are they Muslims?”

Taken aback, the officer said, “as a matter of fact, yes, they are.”

Coreris told the officer he should stop his inquiries about Harris immediately, and that he would be reporting him to the chief. As the patrolman left, Harris gaped at the brazenness of the attempt. He wondered how far the tendrils of this organization really stretched.

The grass in the backyard of 271 Vernon Street hadn’t been cut for months. By spring, it sprouted thick and rough, like wild wheat in a paleolithic savannah, interspersed with dandelions that shed spores into the evening gusts. The rising spores drifted past evergreen trees, which, shaking in the wind, littered the upper layers of the grassland in pine needles. Ladybugs fluttered between the stalks, while earthworms wriggled through the packed dirt below, consuming the detritus hidden beneath the rowdy green carpet.

On April 17, 1974, this natural rhythm was disturbed by a black metal object that pierced through the canopy of pine needles and sank into the grass. At first, it lay almost uncovered, but as time passed, the bent stalks died and new ones sprouted over them, while the wind scattered a patchwork of fallen leaves above. Within days, its brief impression in the urban savannah had been all but obscured. About a week later, when a boy, searching for his baseball, leaped over the chain-link fence into the yard, he didn’t see any unexpected disturbances. He stepped carefully through the dense undergrowth until his foot hit something solid, and then bent over and fished in the grass. Finally, he pulled out what he had found. It wasn’t a ball at all. It was a gun.

Meanwhile, a black Cadillac methodically progressed through the Financial District and Union Square, stopping at every hotel it passed. Two well-dressed black men entered each lobby, telling the receptionist that they were looking for their cousin, another black man, about thirty years old, who was traveling with his wife and infant. Detective Fotinos surreptitiously stood vigil inside one of those hotels, scanning the street for the Cadillac, while Anthony Harris and his family stayed upstairs. Every time a car passed, Fotinos’ heart leapt and his hand reached for his sidearm.

Coreris was trying to arrange Harris’ formal confession. Time was of the essence, as Harris could only be hidden for so long. Eventually, the Cadillac would pull outside of their latest hotel. But Harris refused to give a statement unless he was given a guarantee of immunity. Coreris didn’t have the authority to offer immunity, nor did anyone in his management chain. He could only offer a verbal promise to request it after Harris testified. Harris threatened to retract his confession unless this condition was met. This was an idle threat, and all sides knew it. If Harris ever returned to the streets, he was a dead man. But Harris still refused to concede. This impasse persisted for hours until finally, Coreris resolved to contact the only man who did have the authority to offer prosecutorial immunity.

The patrol officers leaving 271 Vernon knew immediately that the gun they’d been given was related to the Zebra murders. The address was, after all, just a block from the most recent killing. They handed it to the Forensics lab, which compared it to the casings found near Nelson Shields’ body. It matched. That also meant it matched the bullets used in every attack since Tana Smith. But, in a major blow to the investigation, the lab reported that the gun didn’t have any useable fingerprints. The police would have to trace the gun to their suspects manually.

It took hours for Coreris to contact the Mayor. Coreris first tried to contact his office, only to learn the Mayor was in Los Angeles. Then, he tracked down a police officer attached to his staff. That officer, when he was finally reached, promised to locate the Mayor in LA. Finally, at midnight, Coreris received a call from the Mayor. Coreris explained the situation. Alioto permitted himself a long sigh, and then said “Bring the suspect to my office. I’ll be back at 3 AM.”

Efforts to trace the gun started immediately. The ATF, a federal agency, tracked the gun’s origin to a firearms importer in New York, which in turn had sold it to J. C Penney, which then moved it to a store in North Carolina. A discharged army colonel then bought it in 1968. The army colonel then moved to San Francisco, and when he left the city in 1973, he gave the gun to his roommate. Police had found their link to San Francisco. But after this, the trail was hard to follow. That roommate was named Brad Bishop, and he had gone off the grid recently. The army colonel didn’t know where he was, nor did he know anyone who could know where he was. After a few half-hearted efforts, the investigation was temporarily shelved.

At 3:30 AM, Joseph Alioto met with Anthony Harris, his wife Deborah, Harris’ two lawyers, and the two detectives, Coreris and Fotinos. Alioto warned then that even he didn’t have the de jure authority to grant immunity: he could only assure that the government, when making its case, would note the assistance Harris provided and ask the judge for immunity. Harris said he understood. After this latest pronouncement, the room fell silent, and Harris and Alioto looked at each other.

Finally, the tension released. Harris and Alioto shook hands, their interlocking palms forming a bridge over the chasm between them. Coreris and Fotinos released a sigh. All sides had accepted the terms. A tape recorder was started, its gentle whir blunting the silence, and Harris was read his Miranda rights. Three days after he turned himself in, Anthony Harris began his formal confession. Over the next few days, he retold his story, starting from his journey to the Death Angels, to the first murders, to his eventual flight and surrender. This time, Harris gave himself agency. He had helped abduct the Hagues. He had left the car and stood lookout during Saleem Erakat’s murder. And he had shot John Bambic and watched him die. Anthony Harris admitted that he was a murderer. The Zebra team stared in disgust at the man they were now committed to protect. Up until now, the urgency to end the killings had run roughshod over all qualms, but after everyone finally heard the unabridged story—the closest to truth they’d likely ever receive—the cost of this urgency was more apparent than ever.

Three days later, on May 1st, 1974, one hundred police officers assembled in the dark predawn. Anthony Harris’ confession was official and a judge had approved a warrant to arrest the seven men Harris named. The officers divided into assault squads, each assigned to a different location in the city. 844 Grove, where Larry Green and J. C. X. Simon lived. 339 Fillmore, where Manuel Moore lived. The Black Self-Help Moving Company building on Mission. The Nation of Islam Mosque No. 26 on Geary. In silence, officers dispersed to each location, setting perimeters, sealing nearby streets, loading weapons, planning approaches, mapping exits, and shrinking from the slowly encroaching yellow of the sunrise. At 4:52 AM, all radio communication was ended. An unnatural silence ensued, broken only by unintentional shuffling of boots on grass and whispers muffled by clasped hands.

All units moved in at 5 AM. Coreris and Fotinos rushed in with the 844 Grove team. An officer used a crowbar to quickly dislodge the lock before the door was kicked in. Police officers swarmed in, shotguns cocked and ready, clearing the apartment. In the bedroom, they found J. C. X. Simon, sitting up in his underwear, frozen in fear. This man, who believed himself the flag bearer of the Black revolution, who organized almost every Zebra sting, who personally murdered five people dispassionately in the service of his own aggrandizement, did not even question the arresting officers. Without any prompting, he put his hands behind his head and whimpered, “I give up! I give up! Don’t shoot.” Police cuffed him and dragged out of the apartment, while his wife cried softly just behind.

Larry Green didn’t resist either. When Coreris walked over from Simon’s apartment, he found Green handcuffed on the couch, loudly protesting his innocence, while his wife and young child looked on. Manuel Moore was also picked up in his apartment without incident, as were the other four men, who were taken from the moving company or the mosque. The police didn’t, however, find a single gun. Despite Harris’ descriptions of Mosque meetings full of armed men, none of the apartments, nor the moving company, nor the mosque, had any guns. This was a major problem for the investigation. Anthony Harris had named eight men, but could only place five at any crime scene: himself, Manuel Moore, J. C. Simon, Jesse Lee Cooks, and Larry Green. Police were hoping physical evidence uncovered during the arrests could link the four other names as well.

On May 4th, a judge order edited that Thomas Manney, Dwight Stalling, Edgar Burton, and Clarence Jamerson should be released, as there was insufficient evidence to implicate them in the murders. The police now only had one remaining avenue to pursue: the .32 caliber automatic found in the backyard on Vernon. If this gun couldn’t be linked to any of the suspects, then the only evidence they’d have at trial was the testimony of an accomplice and admitted murderer.

They started by revisiting Brad Bishop, the missing roommate who was reported to have owned the gun last. The police compiled a list of every person that had known him in San Francisco and interviewed them. Bishop’s mother said he had moved to Los Angeles to search for work. One other person, an acquaintance, said they’d heard he moved to Honolulu. Both threads were investigated simultaneously. In LA, Bishop’s car was found in a Santa Monica tow lot, where it had been taken after it was left abandoned. No one in the area could remember ever seeing him. In Honolulu, Bishop’s face was plastered on posters, while cops canvassed the city for information. Eventually someone recognized him and Bishop was arrested on gun charges. Bishop, under a threat to be charged for the murders himself, said that he’d sold the gun to a Samoan named Moo Moo Tooa.

Incredibly, through a stroke of sheer luck, police located Tooa in San Francisco after he walked into a pharmacy that one of the Zebra detectives was in. But Tooa, despite endless pressure, cajoling, and blackmail, would not say what he’d done with the gun. He continually insisted he threw the gun into the ocean six months before the murders started. Eventually, Tooa, exhausted from the pressure, left the city unannounced. Two weeks later, while efforts were still ongoing to locate him, he walked out of a movie theater, clutched his chest, and fell forward. Myocardial infarction, fatal, near instant death. The trail truly went dead.

The grand jury met on May 6th, 1974, a week after the arrests. The remaining four accused—Simon, Moore, Green, and Cooks—were formally indicated on May 16th. Bail was set at three hundred thousand dollars, which none of the accused could meet. All four of them plead not guilty, refusing any semblance of cooperation with the authorities, and their trial date was set on July 8th, 1974.

In June, the trial was delayed to September. In August, it was pushed to January. Scheduling conflicts with the defendants’ lawyers, who were paid for by the Nation of Islam, continually postponed the trial through all of 1974. Eventually, in November, a date was set for May 8, 1975—almost a year after the last associated murder.

As the months passed, the terror that gripped San Francisco faded. The attacks finally ended. Tentatively at first, Haight street regained some of its liveliness. North Beach filled on Friday evenings, as people returned to bars and restaurants and clubs. And as the urgency of fear dissipated into mere memory, the public began to critically reexamine at the investigation. Journalists parsed through the public casefile and grand jury testimony, and commented on the number of times the killers slipped through the police’s dragnet, or on the porosity of the many permanent roadblocks and perimeters, and especially, on the absolute ineffectiveness of Operation Zebra. The grand jury testimony mentioned that every single person named by Anthony Harris had been stopped at least once by the Zebra patrols. One of them even had a Zebra card in their possession when they were arrested. The core tenet undergirding the entire operation—that the police could identify the murderers if they were stopped—was a complete farce.

On March 3rd, 1975, Gus Coreris received a call. Arnold George Lucas, a small-time burglar and drug addict, was in prison when he requested an audience with Coreris. Lucas wanted a reduction on his sentence for burglary in exchange for information. “What information?” Coreris asked. Lucas dawdled. The two men negotiated, but Coreris said he needed to hear the information first. Finally, Lucas said that he used to sell guns periodically to Thomas Manney, one of the men recently released from the Zebra indictment. Coreris felt a jab of familiarity and gripped the edges of his chair, trying not to betray his excitement. There was no way, he thought. “Where did you get the guns from?” he asked. Lucas paused, apparently remembering. “I bought them off some guy. Large Samoan, named Moo Moo.”

Moo Moo Tua’s name had never been released to the public, Coreris realized. This had to be genuine. Just two months before the trial, which itself was delayed due to pure chance, the prosecution’s most important evidentiary link had arrived on a lark, from an unrelated prisoner, well after everyone had already given up hope.

Now that the gun’s link to the accused was established, the prosecution could use the gun to place at least one of Simon, Moore, Harris, or Green at the each crime scene. When combined with Harris’ testimony, this created a concrete narrative of the killings that the defense would be hard-pressed to refute. Their primary avenue would be challenging the character of Harris and the other witnesses, and thus disputing the story entirely.

The trial, finally starting on May 3rd, lasted for a full year, until May 9th, 1976. It was the longest criminal trial in the history of California. A hundred and eighty-one witnesses testified, including Richard Hague, the survivor of the first Zebra attack. Anthony Harris testified for twelve days, telling his entire story, including his role in the murder of John Bambic. Larry Green, Manuel Moore and J. C Simon testified as well, as did Arnold George Lucas on his role in buying and reselling the gun.

Finally, the jury, after listening to almost ten months of testimony, began its deliberations. In only eighteen hours, they emerged with an unanimous verdict. All four defendants were found guilty on all counts. The jury believed Anthony Harris. Larry Green, J. C. X Simon, Jesse Lee Cooks, and Manuel Moore were each sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole. Simon stared stolidly at the ground, perhaps contemplating the enormity of the change wrought on his life. Larry Green grinned idiotically and kept looking at his stone-faced wife and silent child standing behind him. Manuel Moore smiled at everyone who looked at him. Together, all three were marched out of the courtroom to the local jail, from where they would eventually be dispersed to various prisons in California to serve out the rest of their lives.

Manuel Moore distanced himself from the Muslims in prison. Supposedly, he used his time to learn to read. He died in San Quentin in 2015 of a heart attack. J. C. X. Simon, the strident Muslim with dreams of power, spent years angling for leadership in the NOI in prison, and as a result, spent much of his confinement in solitary. He died in 2017. Jesse Lee Cooks, who was shunned by the NOI after his guilty plea, quietly spent his years in San Quentin. He died of natural causes in 2021. Larry Craig Green, now 71 years old, is the last Zebra killer left alive. I wonder now, with the majority of his life spent in a metal cage, if he still reflects on the day of his sentencing and smiles. And more so, I wonder what became of his son, whom he left, barely a toddler, to a destitute mother.

The city of San Francisco has changed dramatically since 1974. Two technology booms have completely reshaped the city’s skyline, obscuring many of the art deco skyscrapers in the Financial District behind glittering glass towers about half a mile northeast. Lower Haight, Fillmore, Divisadero, and Hayes Valley, then working-class neighborhoods that the Zebra murderers stalked, are now some of the most expensive in the city. I moved to Hayes Valley a year ago, and as I wrote this article, I walked, many times, across every block and intersection that had been the scene of an attack. The public housing towers have since been demolished and rebuilt into pleasant blocks of pastel-colored townhomes. Imposing condo buildings overlook the region’s eastern edge, while the streets flower with cafes and Asian restaurants and taquerias. Joggers and bikers take the quiet roads west, enjoying the best sunlight in the city.

But the Victorians, I imagine, look just the same: wood-paneled with elaborate molded facades, standing as silent witnesses to generations of human history. The Fillmore district, then a graveyard of exhaust and decaying buildings, has been entirely resurfaced into a quaint neighborhood of bakeries, brunch spots, and new apartments. The Nation of Islam Mosque No. 26 on 1805 Geary Boulevard left the reupholstered neighborhood sometime in the 80s and moved to Fruitvale in Oakland. 1805 Geary has since been rebuilt into a concert venue named “The Fillmore Auditorium.” I saw Alvvays there last October.

But despite this veneer of finality, the story of the Zebra murders cannot yet be closed. With Anthony Harris’ confession, the police were able to attribute fifteen murders and twenty-three victims to Harris, Moore, Green, Cooks, and Simon. Harris’ narrative was supported by the .32 caliber pistol found in a backyard on Vernon street, which could be directly traced to the murderers and placed at each crime scene. But much of the rest of Harris’ narrative cannot be verified. What exactly were the Death Angels? Who was the tall, bearded man who instigated the effort and ran the meetings? How centralized were they? The entire description we have of the cult comes from Anthony Harris, as all of the accused in the case refused to answer any related questions. Harris stated that these meetings were attended by almost thirty men, but he only named eight people. If they were Death Angels too, then what murders did they commit?

And that last question opens a much larger investigation. The Zebra attacks were truly random. The locations were arbitrary. The M.O’s varied between attacks, even for those known to be committed by the same perpetrator. The only unifying characteristic in their victims was their skin color. Indeed, the murders in San Francisco were linked only because the killers only used two weapons and two different cars.

During this same period, there was a spike in random killings of white people across California. There was also an unusual increase in murders of white hitchhikers on California’s major highways. Richard Walley, an investigator in the California Department of Justice, tallied seventy-one murders that could potentially be related to the Death Angels and the Nation of Islam. Clark Howard, the author of one of this article’s major sources, has claimed 271 potential victims.

This idea, of course, accepts Anthony Harris’ description of the cult as a centralized organization with clear leadership. Earl Sanders, an SFPD homicide detective who worked on the Zebra task force, wrote in his book that the Death Angels were a fantasy conjured by Harris to absolve himself of guilt. In Sanders’ view, the “Death Angels” were just a loosely-organized group of radicalized NOI members. There was never an older man directing the murders, nor any elaborate requirements to become a death angel. In this formulation, we have to then question the entirety of Harris’ story. Were there semi-weekly meetings at all? Why was there a pause in the killings? And if Harris and the others were truly independent of the NOI, then why did the NOI try to murder Harris after he became an informant?

Unfortunately, now, half a century since the last murder, and with most of the perpetrators deceased, it’s unlikely we’ll ever have an answer to these questions. Just like Gus Coreris and Jon Fotinos, the rest of the Zebra task force, and the jury in 1975, we’ll have to satisfy ourselves with the incomplete and self-serving recollections of Anthony Harris. I think it’s at least clear that Larry Green, Manuel Moore, J. C. Simon and Jesse Lee Cooks all deserve their sentences. Justice was eventually done, if only in part.

Justice doesn’t, of course, resurrect the murdered or heal the wounds gashing the living. The dead remain in their eternal repose, and as the years grow distant, the memory of them flickers and dims. Those who survived carry scars, psychological and physical, that forever remind of them of their trauma. And, common to all crime victims, they are cursed to be remembered first as victims and second as people. A Google search of any of their names is littered with old news articles, references to their attackers, and details on those fateful months in 1974. About their lives before their murders, about their lives after their attacks, there is almost nothing.

But when I was researching for this article, I found a Facebook page for Paul Dancik, the artist murdered in a phone booth in December of 1973. It’s run by his brother, who has, for decades, cataloged his artwork, sought information on his life in San Francisco, and connected with people who knew him. It’s a beautiful tribute to a man who would otherwise fade anonymously into history, and it will ensure that Paul’s memory, while flickering, will remain alight for a bit longer. For the many other victims, the task of stoking that dying flame passes to the rest of us.

Sources

This is a list of the main sources I used. There are many more historical newspaper articles I used only for small details or isolated quotes that I did not list here for the sake of brevity.

Books

Major sources

Main Historical News Articles

https://www.newspapers.com/article/114542963/sf-police-stumbled-on-missed-zebra/

https://www.newspapers.com/article/114575316/the-zebra-shootings-without-warning/

Miscellaneous